India’s overlooked opportunity in the global trade of used cars

By Ravishankar Kalyanasundaram

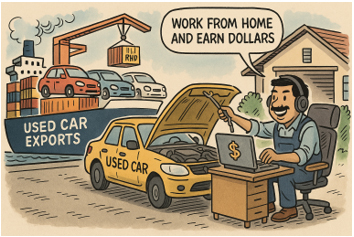

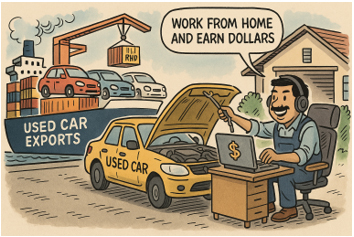

In India, the phrase work from home usually means a coder or a call-centre agent tethered to a laptop. But there is another way of earning foreign exchange without ever leaving the country: refurbishing and exporting used cars. Unlike IT services, this business does not require visas, overseas offices, or fragile trade preferences. It demands something India already has in abundance—mechanics, workshops, and a skilled, cost-effective labour force.

India’s pre-owned car industry is already huge—worth more than $30 billion last year. Yet it remains largely informal, stitched together by small dealers and brokers who thrive on opaque pricing and patchy service. Compare that to America, where CarMax generates $26 billion in sales by industrialising every step of the process, or Europe’s AUTO1 Group, which moves €6 billion worth of cars annually through digital auctions and cross-border logistics. Japan has turned used cars into an export commodity, shipping 1.57 million vehicles in 2024 alone. In these markets, second-hand cars are not an afterthought but a professionalised industry.

India, by contrast, does not export used cars at all. The reasons are depressingly familiar: lack of explicit policy, no uniform certification system, and an absence of institutional push. Most importing countries demand clarity on age, mileage, and emissions. Without a national standard—call it a Pre-Owned Vehicle Export Standard (PVES)—Indian vehicles cannot clear those hurdles. Think of PVES as the equivalent of a star-rating for hotels: a simple, trusted certificate that tells a foreign buyer exactly what they are getting. Thus, a sector that could employ thousands and earn foreign exchange languishes in limbo.

The irony is that demand abroad is booming. Africa’s right-hand drive markets—Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Mauritius, South Africa—rely almost entirely on imported vehicles. They lack local production and even spare-parts industries, making refurbished imports their only realistic option. In Kenya, for instance, over 80 per cent of annual vehicle registrations are used imports, mostly from Japan. The Philippines, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh are similar: they depend on refurbished cars to keep mobility affordable for growing middle classes. In Latin America too—Chile, Peru, Paraguay, Bolivia—imports of second-hand cars sustain transport networks where local manufacturing is absent or limited. The demand is not marginal; it is structural.

If India were to capture even a modest slice of this trade, the economic impact would be striking. Japan today exports over 1.5 million used cars a year, generating billions in foreign exchange. If India were to reach just half that scale—say 750,000 refurbished exports annually—it could mean $8–10 billion in fresh forex earnings. Ports like Ennore, Mundra, and Nhava Sheva would see steady Ro-Ro traffic, creating business for shipping lines, yards, and bonded warehouses. The refurbishing itself would absorb India’s existing auto skills—mechanics, electricians, paint shops, diagnostics—potentially sustaining 100,000–150,000 jobs directly around port clusters. OEMs would gain a structured outlet for trade-ins, NBFCs a cleaner channel for repossessions, and logistics operators a recurring pipeline of movements and parts supply. In short, what is now a grey market could become a formal service-export sector with multi-billion-dollar spillovers.

Russia offers another glimpse of scale. In 2022, 76 per cent of its used-car imports came from Japan, funnelled through Vladivostok. As sanctions squeeze its domestic industry, imports have surged further, with used vehicles now outnumbering new imports in some months. An entire aftermarket ecosystem—from auctions to repair yards—has sprung up in Russia’s Far East.

Here India has a natural advantage. The Chennai–Vladivostok Maritime Corridor, inaugurated in 2024, has cut shipping time from 40 days to just 24. Chennai, often called the Detroit of India, already hosts a dense cluster of auto suppliers, service firms, and OEM exporters. It could easily become a refurbishing hub for cars discarded in Japan or Singapore. Vehicles would arrive at export zones near Ennore or Nhava Sheva, be refurbished by professional groups—TVS, Bosch, Tata’s service networks—and shipped on to Africa, Asia, Latin America, or Russia.

Two revenue streams beckon. First, India’s own used cars, which after five to seven years of domestic life could be refurbished and exported to price-sensitive markets abroad. Second, imported cars from Japan, Singapore and beyond, reconditioned in India and then re-exported. In both cases, India is not competing on raw materials or factory scale but on its comparative advantage: skilled labour at low cost.

The policy ingredients are not complicated. India needs a PVES to grade vehicles, port-based “AutoZones” for refurbishment and quality assurance, and digital auctions to provide transparent price discovery. Banks and NBFCs could channel repossessed vehicles into this stream, improving recovery rates. Export incentives, such as the recently reinstated RoDTEP (Remission of Duties and Taxes on Exported Products) scheme, could provide a modest tailwind. The logistics already exist: ports handle new-car exports with Ro-Ro vessels; the same infrastructure can be extended to certified used cars.

Done right, this would create a service-export industry with multiple knock-on benefits. It would generate employment in port cities, improve balance-of-payments stability, and integrate India into global supply chains now dominated by Japan and trading houses such as Sumitomo. It would also give Indian OEMs a controlled way to manage trade-ins and protect residual values at home.

At a time when tariff wars threaten India’s traditional exports, it makes sense to explore every avenue where the country holds a natural advantage. Cars may not be the first image that comes to mind when thinking about “work from home.” Yet if policy moves with intent, the slogan could acquire a new meaning: refurbish at home, earn abroad.

What India Must Do

If India acts now, it can turn a fragmented domestic trade into a formal service-export industry worth billions, powered entirely by skills we already possess—earning dollars without leaving home. All it requires is one policy announcement: allot idle port-side land, convene the auto makers and service captains, and let them build the ecosystem. India has never lacked entrepreneurial energy in automobiles; it has only lacked a framework. With such a step, our dollar earnings from refurbished car exports could comfortably offset more than 30% of the tariff threat that looms over traditional exports.

Let us, for once, think smart: use the skills we already have, the infrastructure that is already in place, and the global demand that already exists. The world is discarding vehicles every day. India can give them a second life, and in the process, claim a new stream of foreign exchange.