The trend is unsettling, even if the fall appears managed.

By Ravishankar Kalyanasundaram

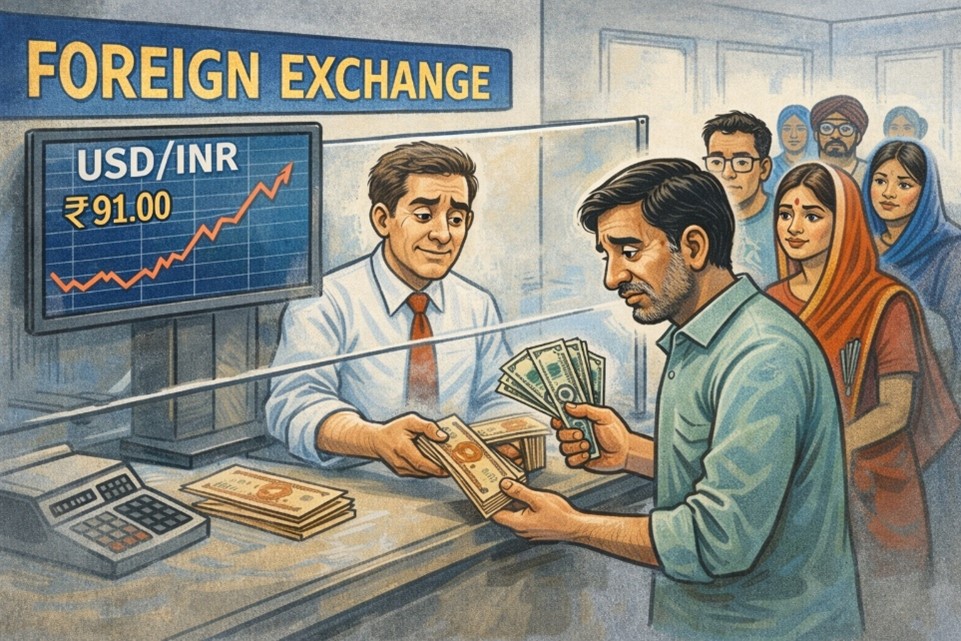

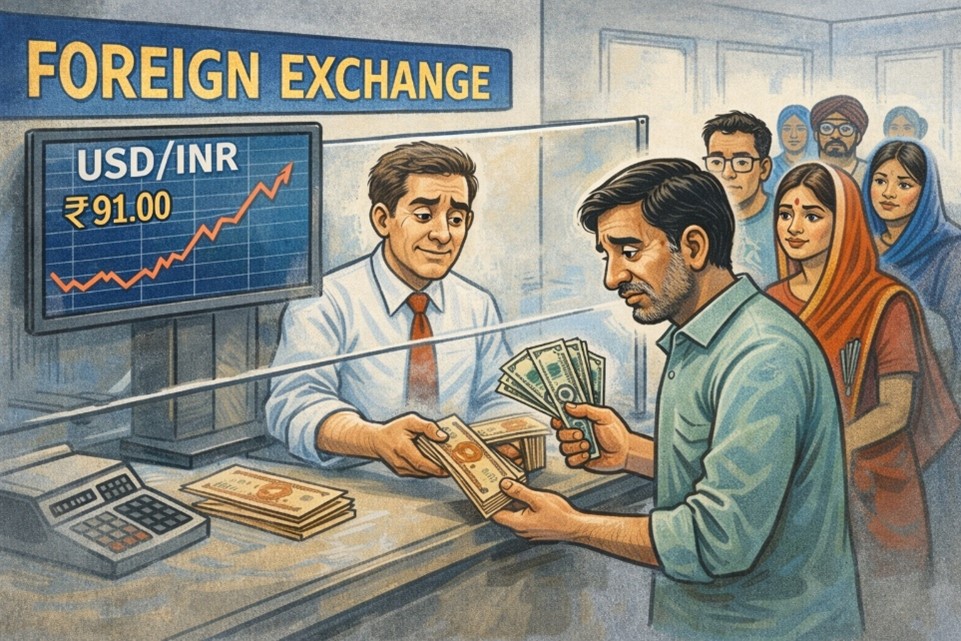

When 2025 dawned, the rupee stood at around ₹83 to the dollar. Today, it is closer to ₹91. That is a depreciation of nearly 10 per cent — not sudden, not disorderly, but unmistakable. It shows up quietly in higher import bills, in overseas education costs, in travel, in the background inflation that households feel before they calculate it. The fall is real.

India is not alone in this. Across Asia, currencies have struggled under the weight of a strong dollar and unsettled geopolitics. The Japanese yen has fallen even more sharply, the Korean won has weakened materially, and several ASEAN currencies have slid in varying degrees. In that sense, the rupee’s story is part of a regional pattern.

But India’s experience carries an important distinction.

This fall has occurred despite sustained intervention by the Reserve Bank of India. Throughout the year, the RBI has sold dollars repeatedly to smooth volatility and slow the rupee’s decline, spending tens of billions of dollars in the process. What we are seeing, therefore, is not a free-market slide. It is a managed descent, cushioned by reserves and careful signalling.

That contrast matters. When a currency ends up in the same depreciation bracket as several Asian peers after heavy defence, the issue is no longer just global dollar strength. It becomes a question of strategy.

The pressure is rooted in flows. Dollar inflows into India have become uneven. Portfolio investors have moved in and out with global risk sentiment. FDI announcements remain healthy, but actual inflows have lagged. Remittances, a historic pillar of strength, remain robust in aggregate but fluctuate month to month. Against this, outflows are relentless and structural — oil imports, defence purchases, electronics, overseas education, tourism, outward investment. This is not capital flight; it is the cost of being a large, globally integrated economy.

In this setting, foreign exchange reserves begin to look less like a stockpile and more like a shock absorber. India’s reserves remain large in absolute terms, but through 2025 they have appeared uneven and wobbly — falling during stress, recovering briefly, then softening again. Each dollar sold buys time. It does not change the underlying balance.

There is also a quieter lever that deserves far more urgency: rupee settlement of imports. For a period, Russian crude imports were officially settled largely outside the dollar system. On paper, this should have conserved tens of billions of dollars and visibly strengthened reserves. That this saving did not fully show up in reserve accumulation suggests gaps in execution or offsets elsewhere — a story for another day. What matters now is the direction of travel. As India shifts back to dollar payments for a bulk of its oil imports, structural dollar demand will rise again, placing renewed pressure on the rupee. In a fractured world, pushing rupee-based trade settlement is no longer a diplomatic experiment; it is a balance-sheet necessity.

Then there is the asset India rarely counts when talking about currency defence.

Indian households hold an estimated 25,000–27,000 tonnes of gold, compared to the RBI’s 800–850 tonnes. Even more striking, roughly 3,000–5,000 tonnes of this gold is already pledged with banks and NBFCs as collateral — assayed, insured, and sitting inside the formal financial system. It supports private credit, but plays no role in national reserve strategy.

It must be said clearly: India has tried to tap household gold before. The Gold Monetisation Scheme and Sovereign Gold Bonds were genuine attempts to reduce imports and channel savings more efficiently. But they were conceived as opt-in savings products, not as instruments of sovereign balance-sheet strategy. They asked households a limited question — would you like to earn a little interest on your gold? They never asked the larger, national one — can your gold strengthen the rupee? As a result, gold remained at the margins of policy, and the RBI stayed a distant observer rather than a strategic buyer.

That distinction now matters.

In today’s world, reserves are no longer neutral insurance. Currencies are weaponised, payment systems are politicised, and capital moves faster than diplomacy. In such an environment, defending the rupee only by selling dollars is a narrowing strategy.

India needs newer methods for newer fears.

A transparent domestic gold repository framework — where the central bank buys gold from domestic holders at market-linked prices, paying in rupees — would strengthen reserves without importing gold or spending dollars. Aggressive rupee settlement of trade would reduce structural dollar demand. A broader conception of reserves, anchored partly in domestic assets and domestic value, would make the rupee less dependent on global mood swings.

The rupee’s journey through 2025 is not a crisis story. It is a warning — and an opportunity. Stability achieved by spending dollars is temporary. Stability built by unlocking value at home is durable.

The question is no longer whether India can defend the rupee.

It is whether India is ready to reimagine how it defends itself.