The quiet arrival of AI co-workers — and why this technological shift may matter more than the internet

By Ravishankar Kalyanasundaram

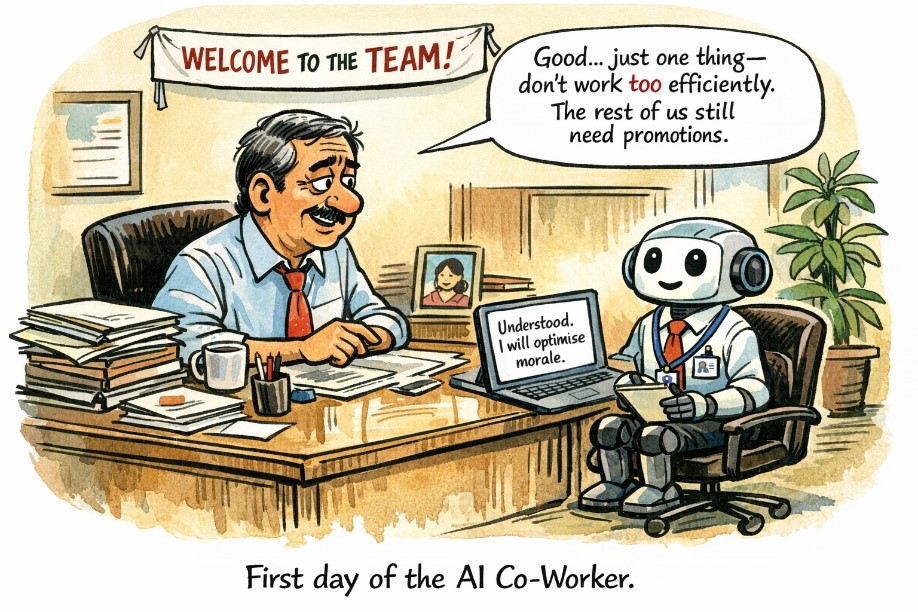

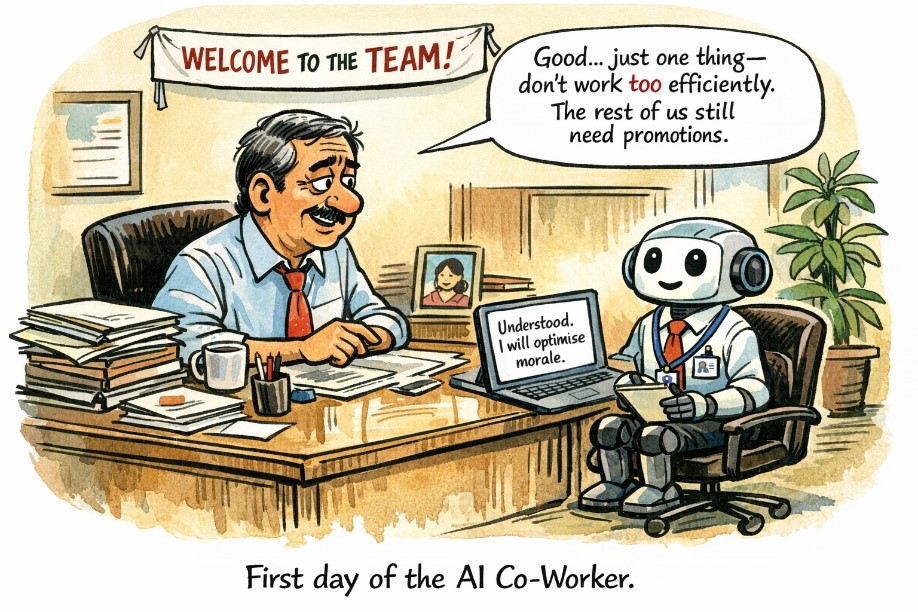

A curious headline has begun appearing in technology columns across the world. A major artificial-intelligence system was no longer being described as a “tool” or an “assistant”. It was being described as a co-worker.

Businesses experimenting with systems such as Anthropic’s Claude are not merely asking them questions. They are assigning them work: reading policy documents, drafting reports, analysing contracts, reviewing code, writing customer responses, preparing research notes, and even planning tasks across departments. In some cases, companies give the system an objective and return hours later to find the first draft already prepared.

The language has quietly shifted.

Earlier, software helped employees.

Now organisations are onboarding something that behaves like a junior colleague.

For the first time, companies are treating a non-human system as part of the workflow rather than a program inside a computer. It has no desk, no salary, and no office ID card — yet it participates in daily operations.

There is a moment in every technological change when society senses something subtle has altered. Not dramatically, not with noise, but with a rearrangement of ordinary life.

The first ATM did not close a bank.

The first email did not end the post office.

The first smartphone did not end the office desk.

Yet over time, all three changed how we lived.

Artificial intelligence may now be reaching that same turning point — but this time the change is not about tools. It is about colleagues.

We have seen revolutions before — but not this kind

Technology has always changed labour. The Industrial Revolution replaced muscle with machines. Textile workers, dock loaders and farm hands gradually gave way to engines, looms and tractors.

Then came computers. In the 1970s and 80s they eliminated ledgers, typewriters and clerical paperwork. Offices did not disappear, but they transformed. One accountant with a computer could do the work of five.

The internet globalised information. Suddenly, knowledge was not local. A small firm in Coimbatore could access the same technical manuals as a corporation in London. Geography lost some of its power.

Mobile networks changed something even more personal. Work stopped belonging to a place. It followed the worker home. The office shifted into the pocket.

Robotics altered factories. Physical labour began declining in manufacturing. Automation became an accepted part of production.

Yet through all this, one area remained uniquely human: judgement.

Machines calculated. Humans decided.

That boundary is now blurring.

Why AI co-workers are different

Earlier technologies replaced tasks.

AI co-workers replace portions of roles.

A spreadsheet replaced arithmetic.

A robot replaced lifting.

An ERP system replaced paperwork.

But an AI co-worker can assist — and sometimes perform — parts of a professional’s daily thinking.

A junior lawyer may now review an AI-drafted contract instead of writing it.

A software engineer may supervise code rather than type every line.

An analyst may validate a report rather than prepare it from scratch.

This is not automation of labour. It is augmentation of cognition.

For the first time, a technology directly enters the service sector — the very sector that absorbed millions of workers after agriculture and manufacturing mechanised. That is why economists see this moment as different from the internet boom. The internet changed markets. AI may change employment structure.

What will actually happen inside offices

The immediate impact will not be mass unemployment. It will be something less visible but more profound.

Teams will shrink quietly.

Hierarchy will flatten.

Speed will increase.

A department that required ten people may require five. A company that needed a week to prepare a report may need a day. Middle layers of supervision — reviewing, summarising, reporting — will slowly fade because machines can monitor continuously.

For managers, the change will first appear as efficiency.

For employees, it will appear as pressure.

Work will shift from producing information to validating it. The value of a professional will depend less on how much they know and more on how well they interpret machine-generated output.

The skill that rises is not memory. It is judgement.

The global race will not be about software

Every major technology eventually becomes a national capability. Electricity grids, railways and telecom networks were not merely industries — they became strategic infrastructure.

Artificial intelligence is moving in the same direction.

The United States will adopt rapidly because productivity translates directly into competitive advantage. Europe will move cautiously, balancing labour protection and regulation. China will embed AI across manufacturing and governance as state infrastructure.

For countries like India, the situation is more delicate.

India’s particular dilemma

India’s growth over three decades relied heavily on skilled services — IT support, accounting, consulting, analytics and business processing. Millions of young graduates found employment precisely because the world outsourced routine knowledge work to India.

AI co-workers now perform many of those tasks efficiently.

This does not mean jobs vanish overnight. But it does mean opportunity changes. Routine work will decline. Supervisory and creative work will grow.

If adopted early, the same technology could improve courts, healthcare, education and small business productivity. But that requires viewing AI not only as a corporate efficiency tool, but as national capability — much like broadband connectivity a decade ago.

A change in what creates value

For most of history, production depended on labour and capital. A company grew by hiring more workers or buying more machines.

In the coming years, growth may depend on how effectively organisations combine human and artificial intelligence. A small team using AI intelligently could outperform a much larger organisation relying only on human processes.

Scale may matter less than adaptability.

The human question

Every technological change creates anxiety. When ATMs arrived, bank employees feared redundancy. When computers entered offices, typists feared extinction. Instead, roles evolved.

The same will likely happen again — but the transition will be uncomfortable.

Education must shift from memorisation to reasoning.

Careers will move from execution to supervision.

Expertise will increasingly mean knowing what to ask, not just what to answer.

The central skill of the future workplace may be discernment — the capacity to question, interpret and take responsibility for decisions made alongside machines.

Moment for Institutions to adapt

Within a decade, AI co-workers may become ordinary. Offices will include them as naturally as they include email systems today. Yet we are living through the short, unsettled period before that normalisation — the moment when institutions must decide how to adapt.

The industrial revolution mechanised labour.

The digital revolution connected information.

The AI revolution may reshape decision-making itself.

And decision-making is the real power inside economies.

The question therefore is not whether machines will replace humans. Most likely, they will not. The deeper question is whether societies, companies and governments can redesign work, education and responsibility quickly enough for humans and intelligent machines to operate together.

For the first time in history, productivity will not depend only on how hard we work, or even how smart we are, but on how wisely we choose to work with intelligence we did not create through human experience.

The future workplace may still have desks, meetings and deadlines.

But one of the colleagues will not go home in the evening — and the success of the organisation may quietly depend on how well the humans learn to work with it.