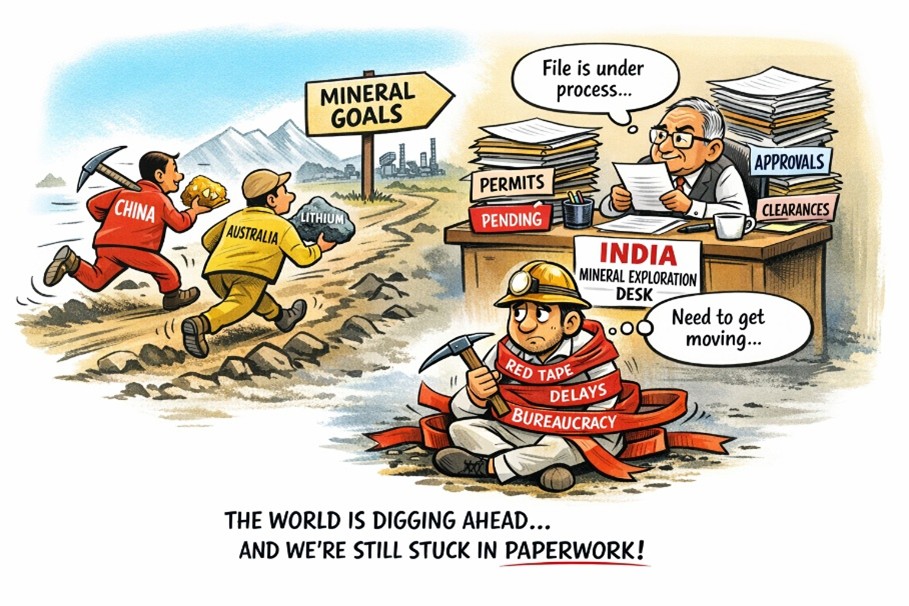

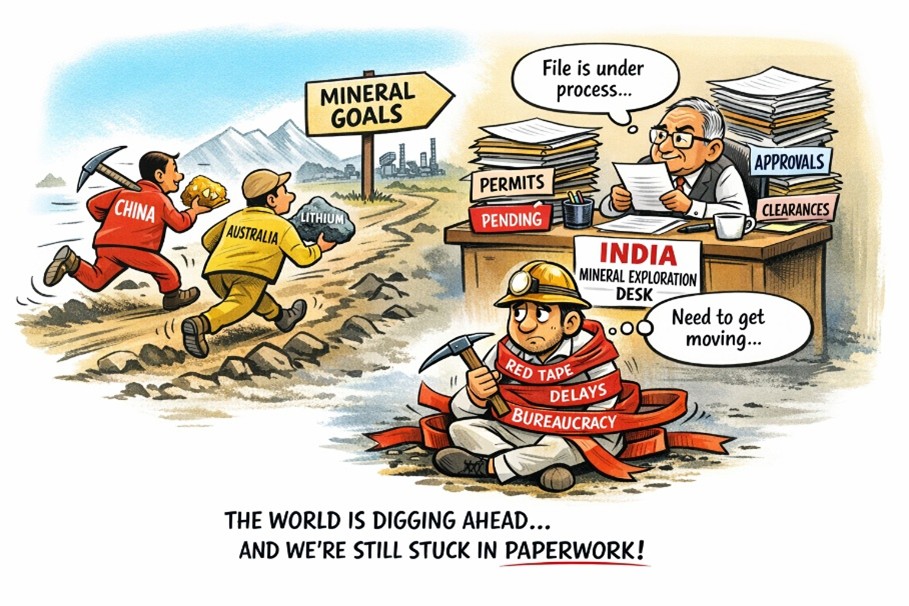

In a race where minerals shape economic power, time lost after discovery may matter as much as discovery itself.

By Ravishankar Kalyanasundaram

The news surfaced quietly. Media reports said China has discovered a gold deposit beneath the seabed — its first such find, and possibly among the largest in Asia. There was no spectacle, no political flourish. Just another data point in a long pattern.

It felt expected. China has been exploring aggressively — on land, abroad, and now beneath the ocean — driven by a clear understanding that minerals are no longer just raw materials. They are inputs into economic power.

India’s own lithium story illustrates the challenge starkly. Lithium-bearing geology in Jammu & Kashmir was first identified as early as 1999 during regional surveys. Yet it took more than two decades for this to translate into a formal resource declaration. Only in February 2023 did the Geological Survey of India announce 5.9 million tonnes of inferred lithium resources in the Reasi district. As of now, the deposit remains at an early stage — exploration refinement, auctioning and commercial production are still ahead. In contrast, China’s undersea gold discovery has moved swiftly from exploration to confirmation, backed by technology, funding and institutional coordination. The comparison is not about capability, but about tempo. One system compresses time between discovery and deployment; the other allows it to stretch into decades. Lithium is, after all, the backbone of electric vehicles, batteries, grid storage and future mobility.

Two discoveries. Two countries. Two very different trajectories.

The Moment That Demands Comparison

China’s find signals intent. India’s signals potential.

And in today’s world, the gap between intent and execution is where nations either move ahead — or fall behind.

Minerals were once associated with steel plants, cement factories and mining towns. Today, they sit at the intersection of technology, geopolitics and industrial strategy. Electric mobility depends on lithium and nickel. Renewable energy depends on copper and rare earths. Defence systems, space platforms, semiconductors and AI infrastructure all rest on mineral-intensive foundations.

Countries that recognise this are not waiting.

China built dominance not merely by mining minerals, but by controlling exploration, processing, refining and data. Australia followed a quieter path — building credible geological knowledge, predictable approvals and investor trust over decades. Canada did the same. Even the United States, having neglected this space for years, is now openly anxious about its dependence and scrambling to catch up.

India, watching this unfold, appears to be standing at a fork in the road.

From Discovery to Delivery: India’s Slow Corridor

India is not a mineral-poor country. Iron ore, bauxite, coal and limestone are well established. Rare earths line our coasts. Lithium has now been identified in Jammu & Kashmir. The problem has never been absence.

The problem has been follow-through.

Public discussions often note that only a small fraction of India’s geological potential has been explored in depth. Whether that figure is 8 per cent or 12 per cent is less important than the pattern it reveals. India explores cautiously. And after discovery, it often pauses — sometimes for years.

In another era, such delays may have been tolerable. Today, they are costly.

When Time Becomes the Fatal Constraint

Two cases from recent history illustrate this painfully well.

The first is POSCO. Announced in 2005, the proposed $12-billion steel plant and iron-ore linkage in Odisha was among the largest foreign investment proposals India had ever seen. The logic was sound: assured raw material, employment, downstream industry, exports.

What followed was nearly a decade of procedures — environmental hearings, land issues, protests, legal challenges, policy shifts at both state and central levels. By 2016, POSCO withdrew. The ore was still there. The demand was still there. But patience had run out.

The second case is quieter but equally revealing: Rio Tinto’s Bunder diamond project in Madhya Pradesh. Discovered in the early 2000s, it was among India’s most promising diamond deposits. After years of exploration and planning, approvals stretched endlessly. In 2016, nearly 15 years after discovery, Rio Tinto exited India, selling the project and winding down its exploration ambitions.

In both cases, geology did not fail.

Economics did not collapse.

Time did the damage.

These exits were not ideological statements. They were signals. They told global investors that India’s system struggles not with rules, but with resolution.

Why Does This Keep Happening?

From an observer’s seat, the reasons appear less technical and more structural.

First, there is layered regulation. Mineral development in India must pass through central ministries, state governments, environmental authorities, land and forest processes, judicial scrutiny and local consent mechanisms. Each is legitimate. Together, they often operate sequentially rather than in coordination.

Second, there is centre–state friction. Minerals sit underground, but authority sits above it — divided between states that own the resource and the Centre that regulates extraction, environment and trade. Alignment is slow, and delays multiply.

Third, there is bureaucratic risk aversion. In a system where files can be questioned years later, delay often feels safer than decision. But in a fast-moving global economy, delay is no longer neutral. It is a decision — and usually a costly one.

Finally, there is the absence of time-bound closure. Projects are rarely given a clear yes or no. They remain suspended — long enough for capital, technology and opportunity to move elsewhere.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

Development today is no longer driven by intent alone. It is driven by technology cycles and geopolitical competition. Supply chains are being redrawn. Energy transitions are accelerating. Strategic minerals are becoming instruments of leverage.

In this environment, bureaucratic files cannot be the final answer.

A country may have satellites in orbit and digital platforms serving a billion people — but if it cannot move from mineral discovery to production in reasonable time, it risks building its future on external dependence.

China’s seabed gold discovery and India’s lithium find in J&K should not be read as isolated headlines. Together, they frame a question: do we have the institutional speed to match our ambition?

An Unfinished Choice

This is not an argument against environmental protection or community rights. Those are essential. But preparedness is essential too.

Minerals are no longer just raw materials. They are inputs into economic sovereignty. Discoveries that remain stuck in procedure are announcements, not assets.

India still has time — but not unlimited time.

In a race where minerals shape economic power, time lost after discovery may matter as much as discovery itself.

The world is moving at the speed of technology and geopolitics.

India must decide whether its systems can keep pace — or whether procedure will continue to outrun purpose.