Dollar dominance and military might keep the Western order intact, while Asia’s counter-bloc offers political solidarity but struggles to build economic depth.

By Ravishankar Kalyanasundaram

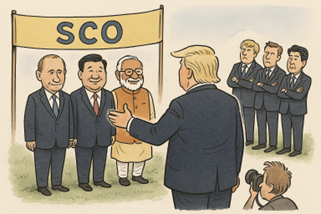

The image from Tianjin will endure: Xi Jinping on stage flanked by Vladimir Putin and Narendra Modi, with Kim Jong-un making his first international appearance in years by train from Pyongyang. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit, staged with ceremony and symbolism, looked less like a regional conclave and more like an attempt to sketch a parallel order.

Xi spoke of a new global security and economic framework centering the “Global South.” He urged the creation of an SCO development bank and funding mechanisms that would insulate members from Western leverage. Putin welcomed the call, reaffirming his long-standing theme of multipolarity. Modi’s presence, carefully calibrated, gave legitimacy to the gathering without binding India too tightly. And Kim’s cameo, though largely theatrical, underscored solidarity among those long excluded from Western institutions.

The message was clear: if Washington builds walls through tariffs and sanctions, Asia and its partners will build alternative corridors.

Trump’s West: Strengths and Shadows

President Donald Trump’s second term has brought tariffs into the centre of global strategy. Europe, though uncomfortable, falls in line — preferring U.S. security guarantees to confrontation.

The West retains formidable strengths. The dollar remains the deepest and safest financial pool. NATO’s military umbrella is unmatched. And the Federal Reserve, despite political interference, still anchors the world’s money markets.

But there are shadows. Tariff wars distort supply chains. Sanctions and technology bans weaponize finance. Europe’s search for autonomy ends with reluctant dependence. The paradox of Trump’s West is this: overwhelming strength coupled with diminishing trust.

Why the Global South Looks Elsewhere

For many outside Europe, multipolarity is not an ideological dream but a practical necessity. Dollar loans have trapped nations in repayment crises. Commodity imports expose them to volatility they cannot control. And sanctions remind them that one diplomatic misstep can cut them out of the global system.

Seen from Nairobi, Colombo, or Manila, Xi’s call for new institutions looks less like defiance and more like common sense. Political solidarity becomes survival strategy.

The Xi–Putin–Modi–Kim Bloc: Politics Over Economy

The bloc that assembled in Tianjin projects strength, but mostly of the political kind.

It offers legitimacy for nations tired of Western lectures, and dignity in the form of equal voice. It rallies those who feel targeted by sanctions and tariffs.

Yet its weakness is just as clear. China and India remain rivals more than allies. Russia’s war economy leaves it isolated. Kim’s symbolism adds theatre, not substance. Alternative currencies and credit pools remain shallow.

This bloc can stage impressive political shows. What it cannot yet do is build the economic muscle to rival the dollar-led system.

When Rhetoric Meets Reality

Consider a scenario debated by regional media: Israel engages Iran and American bombers strike suspected nuclear facilities. If Iran were by then a full SCO member, the response would test the bloc’s purpose. Would its members attempt to restrain Washington? Through military show of strength, coordinated diplomacy at the UN, or economic counter-measures?

None of these paths are straightforward. A military pushback would risk escalation with the U.S. and its allies — a step no capital could take lightly. Institutional manoeuvres would also be limited: the SCO has no sanctioning authority, no stabilisation fund, and no tested mechanism for crisis response. Economic gestures — boycotts, currency moves, trade corridors — may sound bold, but the dollar remains the nervous system of global commerce.

Yet silence carries its own risks. Failure to respond could expose awkward differences within the bloc. Beijing’s caution is not Moscow’s defiance; Delhi’s balancing act is not Pyongyang’s theatre. What begins as solidarity can quickly turn into compromise, even fracture.

These would not be fatal blows but moments of embarrassment — reminders that building an alternative order requires not only rhetoric but also institutional depth.

The Shackles on Multipolarity

Why, then, does the “logical step” of multipolarity remain unfinished? Because two forces still hold the field.

The dollar, with its unrivalled liquidity, is where the world still runs in times of crisis — even those who resent U.S. dominance. And American military power, spread across oceans and alliances, continues to guarantee the very sea lanes through which Asia’s trade flows.

Politics can flirt with alternatives, but economics and security drag nations back to Washington.

India as the Pivot

India embodies this global dilemma. Modi’s presence in Tianjin symbolised openness to alternatives. Yet India’s growth remains tied to Western markets, technology, and investment. Delhi cannot detach from the QUAD, nor can it ignore the SCO.

India hedges, balances, and manoeuvres — seeking autonomy without rupture. If multipolarity does come to pass, it will be India’s careful steps, as much as China’s ambitions or Russia’s defiance, that shape its course.

Two Incomplete Orders

What we are left with are not two coherent systems but two incomplete ones.

Trump’s West: deep in economics, overwhelming in force, but politically coercive.

The Xi–Putin–Modi–Kim bloc: bold in politics, resonant for the Global South, but economically shallow and internally divided.

Multipolarity is logical, perhaps inevitable. But logic alone cannot overturn liquidity and force. For now, the world must live with two half-finished orders — each restraining the other, each vulnerable to its own contradictions.

The observer’s conclusion, then, is less about winners and losers and more about pathways. The West carries power without trust; the emerging bloc carries trust without power. Between them lies a world not yet ready for a new order, stumbling between two, unfinished and uncertain, compelled to balance on both sides of the divide.