How 60,000 Acres Came Back Into View—And What We Might Do With It

By Ravishankar Kalyanasundaram

Recently, media reports mentioned that nearly 60,000 acres of government-owned salt land—long overlooked—would now be leased for what are being called strategic purposes. These include renewable energy, industrial zones, eco-tourism, and affordable housing. It’s the kind of announcement that draws quiet optimism. There’s no shortage of demand for land in India, and these coastal parcels—if they are indeed free from legal and environmental encumbrances—could potentially ease the way for clean infrastructure.

But as always, one can’t help but wonder: where was this land all along? And why now?

Salt Lands: A Forgotten Asset

The story of these lands goes back to the colonial era, when salt production was a major economic activity along India’s coasts. Vast stretches of flat, sun-exposed terrain were used for solar evaporation. The Salt Commissioner’s office managed them, and they remained under central government control long after their economic role faded.

With the advent of modern desalination and chemical production methods, these traditional salt lands became redundant. And yet, they were never meaningfully repurposed. Many simply disappeared into the quiet interiors of government files—suspended in layers of lease renewals, overlapping jurisdictions, and the familiar weight of procedural caution.

What the Policy Says—and What It Doesn’t

According to the October 2024 policy, PSUs can now lease these lands at 50% of guideline value, while infrastructure projects may qualify for even steeper discounts—just 10% of circle rates in some cases.

That’s a notable gesture. But it does seem to lean heavily towards public sector undertakings and state-led agencies. There is, at least from what’s visible so far, no structured path for private developers to participate directly. If the intent is to unlock value quickly and at scale, one might have expected a broader framework.

In a country where many asset monetisation initiatives have faced legal delays or tepid investor response, the choice of institutional channel matters. One hopes this effort will avoid the common fate of promising schemes that stall in silence.

A Look at the Map

Of the reported 60,000 acres, Andhra Pradesh holds around 20,700 acres, Tamil Nadu about 17,100, and Maharashtra more than 12,000—including a tightly held 5,400-acre parcel in Mumbai that remains restricted by multiple overlays.

These are not remote or agriculturally sensitive lands. They are coastal, contiguous, largely flat, and in government ownership—a rare combination in today’s development landscape. In theory, such land parcels could be put to use quickly. But as observers of Indian policy would know, land that is legally clear is not always administratively ready.

There Have Been Precedents

Some progress has been made in the past. For instance, L&T’s port at Kattupalli, near Chennai, was developed on reclaimed salt land. It remains a useful example of what can happen when administrative clarity and private initiative find common ground.

But such examples are relatively few. In many other regions—Mundra, Ennore, Palghar, Raigad—similar parcels have remained unused, or slowly absorbed into the fog of encroachments, legacy leases, or ecological concerns.

What Could Be Done

If one were to speculate constructively, these lands could support solar farms, green logistics hubs, and even climate technology zones. Given their saline soil and CRZ-related development constraints, they may not be suitable for traditional construction. But for solar energy, they might be ideal.

Rough calculations suggest that at 4 acres per megawatt, these lands could generate over 15,000 MW of solar power. That’s not insignificant. At current cost structures, this could potentially attract upwards of ₹70,000 crore in private investment—with the government contributing land as equity and retaining long-term value.

The idea of creating a dedicated public entity—a sort of Salt Land Development Corporation—has been floated in policy circles before. If designed thoughtfully, such a platform could offer a structured way to tender land on a PPP basis, with clear timelines and performance guarantees.

But Will It Happen?

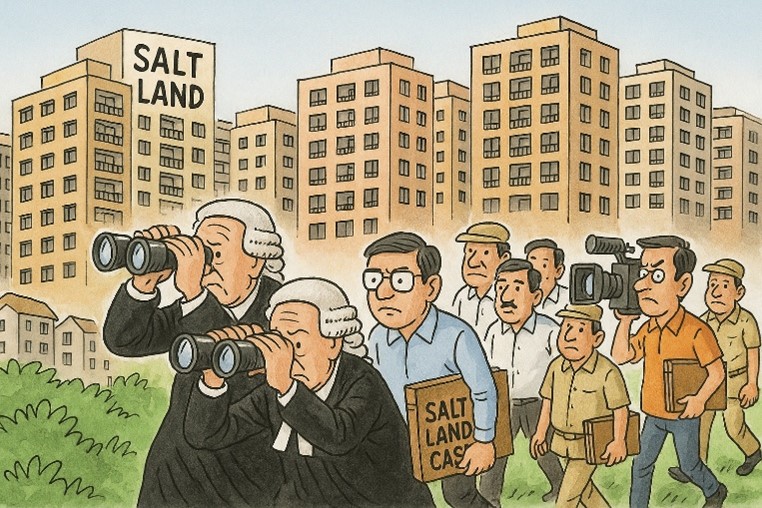

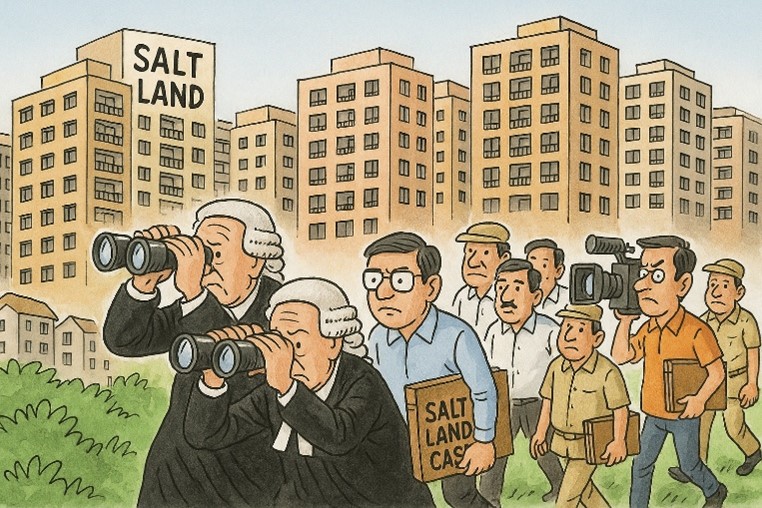

It’s difficult to say. India’s track record with large public land assets has been mixed. From disappearing lakes in Bengaluru to encroached riverbeds in Chennai, the gap between land policy and land use remains wide. Many parcels have ended up as case studies—not in development manuals, but in courtrooms and audit reports.

This doesn’t mean the salt lands are fated to the same outcome. But without focused, single-agency leadership and transparency, they may struggle to find a viable future.

A Modest Suggestion

Perhaps it is time to think of these lands not as liabilities, but as legacy assets waiting for relevance. With India chasing an ambitious renewable energy target, and coastal states looking for industrial and environmental solutions, there is space here for practical imagination.

One doesn’t need grand reinvention. Just a bit of urgency, and a willingness to clear the fog of forms, files, and footnotes.

Salt, after all, once built empires. With care, it might still light up a few towns.