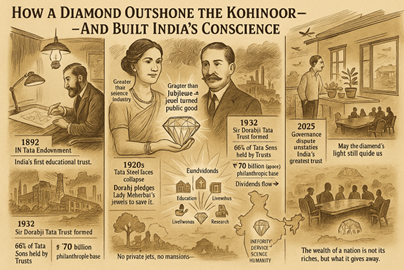

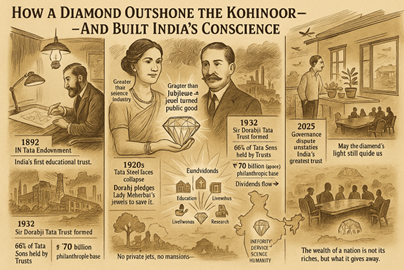

How India’s greatest philanthropic trust became both its pride and its dilemma

By Ravishankar Kalyanasundaram

The past few weeks have been uneasy in Bombay House. Reports of disagreements among trustees of the Tata Trusts, the powerful body that owns two-thirds of Tata Sons, have unsettled the country’s most admired industrial house. Meetings in Delhi between Noel Tata, N. Chandrasekaran, and senior ministers have only added to the intrigue. The precise cause — questions of appointments, governance, or future direction — remains unclear. But the unease has reminded India that the Tata Trusts are not merely shareholders; they are the moral spine of Indian capitalism.

For more than a century, the Trusts have stood for a rare idea — that private enterprise can serve public purpose. Their dividends fund hospitals, research institutions, and scholarships. Their legacy is not built on control, but on conscience.

A Vision Born Before Its Time

It all began with Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata, who in 1892 created the JN Tata Endowment to help Indians study abroad, at a time when higher learning was a privilege of the few. He dreamt of an India where science would lead industry, not follow it. In the late 1890s, frustrated that he had to recruit foreign engineers for his mills and mines, Jamsetji conceived of a national research university — the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore.

He wrote to Lord Curzon that the nation’s progress “can only be assured when its best minds are trained in laboratories, not in libraries.” The idea was revolutionary — long before the Massachusetts Institute of Technology became a global model, India’s first industrialist had already imagined its equivalent. Decades later, the IISc would become a cradle for the country’s scientific leadership, built on the same principle that powered the Tata Trusts: knowledge and enterprise must return dividends to society.

The Diamond That Outshone the Kohinoor

After Jamsetji came his two sons, Sir Ratan Tata and Sir Dorabji Tata, who turned their father’s vision into enduring institutions. Ratan founded his trust in 1919 to promote education and social reform. Dorabji went further, writing philanthropy not into a deed but into destiny.

In the 1920s, when Tata Steel struggled for survival amid falling prices and global recession, Dorabji and his wife, Lady Meherbai Tata, did the unthinkable. They pledged her jewels — among them the legendary 245-carat Jubilee Diamond, larger even than the Kohinoor — to raise funds and keep the company alive.

It was an act of faith that glittered brighter than any gem. The diamond, sold after their deaths, seeded the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust in 1932. From its proceeds rose the Tata Memorial Hospital, the Indian Institute of Science, and a tradition of public giving that defined the modern Tata ethos. The Jubilee Diamond became India’s most luminous metaphor — a jewel turned into justice, private treasure turned public trust.

A Fortune That Funds a Nation

Few realise the scale of this quiet philanthropy. The Tata Trusts today own about 66 per cent of Tata Sons, the holding company of a group whose combined value exceeds US $300 billion. Through Tata Sons, the Trusts hold controlling stakes in Tata Consultancy Services, Tata Steel, Tata Motors, Titan, Tata Power, and more. Their share of profits, which could have enriched individuals, instead feeds a vast philanthropic pipeline — from cancer care networks and water conservation to rural livelihoods and scholarships for students across India.

In pure economic terms, the Trusts’ asset value rivals that of the world’s greatest foundations — the Gates, Rockefeller, or Getty. Yet their model is uniquely Indian: philanthropy built into ownership, not added as afterthought. Every rupee of dividend from TCS or Tata Steel becomes a drop in the country’s social reservoir.

The Simplicity of Greatness

If the wealth was extraordinary, the men who guarded it lived with disarming humility. J. R. D. Tata, the aviator-industrialist who built Air India and shaped post-independence Indian industry, lived all his life in a modest two-bedroom flat on Altamount Road. He had no private plane, no escort convoy, no gilded mansion. When he travelled, he often drove himself. Ratan Tata, who succeeded him, inherited the same quiet grace — seen often in the small gesture of stopping to feed a stray dog at his office gate.

This restraint was not affectation; it was culture. The Tatas built empires without entitlement. They saw prosperity as a means, not an end.

The Conflict and the Hope

That is why today’s governance dispute troubles many Indians beyond the business community. For the Tata Trusts are not merely a corporate entity — they are a public institution built on private sacrifice. Their credibility rests not just on performance but on purpose.

One hopes the trustees will remember what their founders stood for: that wealth, when consecrated to the public, demands humility in stewardship and harmony in spirit. The Tatas have never been just a business; they have been a moral compass for what business in India can mean.

A Legacy Meant to Endure

When Jamsetji sent his first scholars abroad, when Lady Meherbai gave up her diamond, when J. R. D. refused luxury, they were not merely building a group — they were crafting a philosophy. That capital must carry compassion, that institutions must outlive individuals, and that India’s progress is safest when guided by conscience, not control.

As the Trusts navigate their present storm, the nation watches with respect and expectation. For the diamond that once saved Tata Steel did more than rescue a company — it set a benchmark for an entire civilisation. If today’s custodians can find unity in that spirit, the Trusts will not only survive this test; they will, once again, outshine the Kohinoor.