The Bihar Mandate and the Annuity Republic

By Ravishankar Kalyanasundaram

On television, last night looked like a festival. Orange flags, drums, motorbike parades, leaders standing in jeeps with garlands thick enough to hide the fatigue beneath their smiles. Delhi’s fireworks joined Patna’s, and the anchors spoke in a breathless staccato — “landslide”, “historic mandate”, “decisive verdict”. But beneath the neon lights and the sound of celebration, the ticker told the quieter truth: the NDA had captured 202 of Bihar’s 243 seats, turning one of India’s poorest states into its newest political trophy.

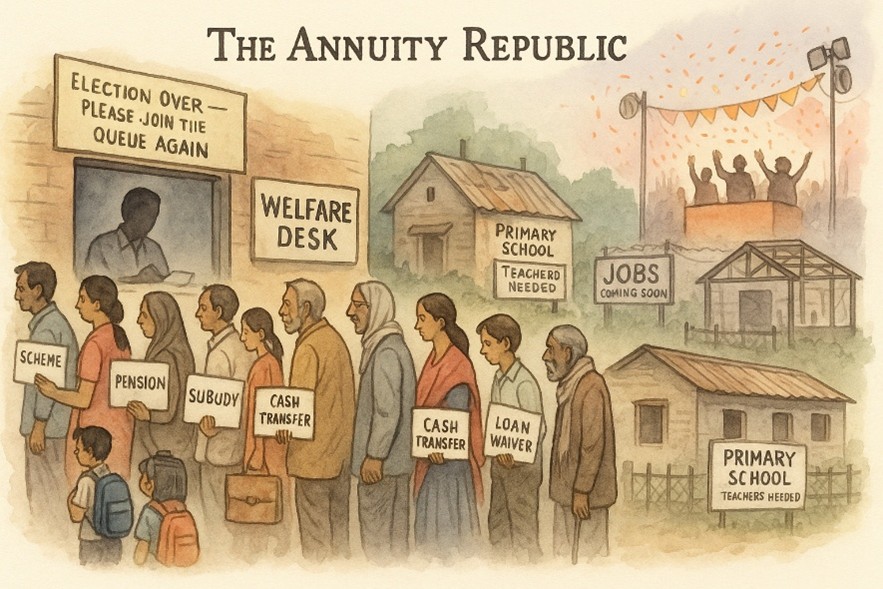

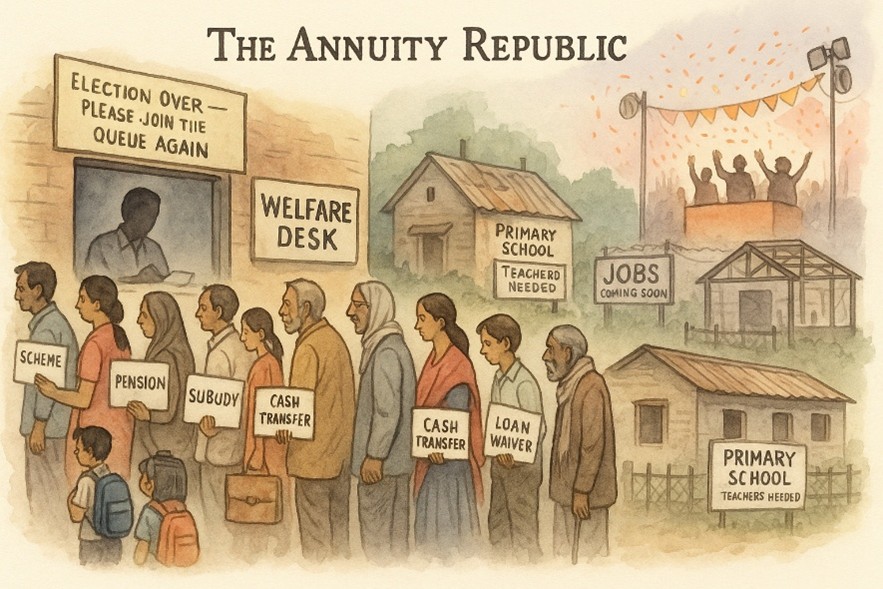

Mute the television, step into a village in Gopalganj or Saharsa, and the soundscape shifts. Elections here are not a contest of ideology; they are the annual budget of survival. Will the cash transfer to women continue? Will the old-age pension go up? Will the government add more names to the housing list? Will there be another loan waiver, another recruitment, another cooking-gas subsidy? A land that once produced Nalanda, Pataliputra, the Arthashastra and Ashoka’s edicts is today reduced to a queue for schemes — a Republic reimagined as an annuity.

The numbers behind this “welfare race” are staggering. Between state schemes, Union transfers and election-season accelerators, Bihar’s governments now disburse tens of thousands of crores each year as direct benefits. This election alone saw a massive push: an employment-linked transfer to women that funnelled over ₹75 billion into their accounts. It improved lives in the short term, no doubt. But look closely at the ledger — who pays for this continuous rainfall of cash? Not Bihar. Three-quarters of Bihar’s revenues come from New Delhi. Its own tax effort contributes barely 26%. And the rest — the welfare, the roads, the schools, the pensions — is funded by the taxpayer outside Bihar: you, me, the salaried worker in Chennai or Bengaluru, the small business in Surat, the start-up engineer in Hyderabad.

This is the political economy of Bihar: a state on central life-support. The 15th Finance Commission raised Bihar’s share of central taxes from 9.7% to 10.1% — a gesture of solidarity, but also an admission that Bihar cannot finance its own developmental future. Its debt-to-GSDP ratio is brushing 40%, higher than the median Indian state. Its fiscal deficit hovers at the edge of prudence. Every new manifesto promise — jobs for each family, universal stipends, free coaching, free cycles, free uniforms, free everything — rests on ground that is already cracking.

Against that backdrop, the victory euphoria feels oddly hollow. Because the real question is not who wins the election; it is who pays for the victory. An entire state is caught in a cycle where politics manufactures poverty, and poverty manufactures pliant politics.

And yet, Bihar was not always like this. It is one of the world’s oldest intellectual homelands — the soil of Buddha, Ashoka, Chandragupta Maurya, and Chanakya; of caravans that crossed Asia seeking Nalanda’s libraries; of dynasties that mapped the subcontinent before Delhi even dreamt of power. To place that history next to today’s indicators is almost indecent.

Per capita income in Bihar is barely ₹66,000 — a third of the national average. Literacy is still stuck at 61.8% against India’s 73%. Gross enrolment in higher secondary and college is far below the national curve. Even today, nearly 88% of Biharis live in rural areas, almost half work in low-productivity agriculture, and only about 6% find a foothold in manufacturing. Three-quarters of north Bihar is flood-prone, yet several districts also face water scarcity. Forest cover is low, landholdings fragmented. And 73% of rural households are classified as deprived across multiple dimensions — education, housing, sanitation, income, and security.

Behind each statistic lies a choice no citizen should be forced to make. When the Kosi floods or a canal breaches, children lose a year of schooling. Families migrate to Delhi’s construction sites or Surat’s dyeing units, returning only for elections and funerals. The OPD queue in Madhepura is not a line; it is a verdict on governance. The labour line at Muzaffarpur station at 5 a.m. is not migration; it is exile. And the first-generation learner opening a textbook in a government school is not a success story; she is a survivor.

To be fair, Bihar has not stood still. Roads have improved dramatically since the early 2000s. Many districts now have paved highways, better connectivity, more electrified homes, more mobile penetration. Infant mortality has fallen; immunisation has risen; girls’ enrolment has climbed. Bihar’s economy grew at over 9% last year — one of the fastest in India. But development is not a race of averages. The real measure lies in the opportunities created for the young.

Has Bihar turned its demographic dividend into a skilled workforce? Has it built enough ITIs, polytechnics, nursing colleges, teacher-training institutes? Has it attracted labour-intensive industry at scale — not small, scattered units but full ecosystems like Aurangabad or Tiruppur or Sanand? Has it created a climate where entrepreneurship can flourish without navigating caste networks, crime syndicates or political patronage? On these fronts, the record is painfully thin.

Which is why the celebration last night felt like a repeat telecast. Bihar has seen many such nights. But what do the mornings feel like? What happens after the crackers burn out and the victory jeeps go home? In the villages, the questions begin again: who gets the ration card, who gets the pension, who gets the scheme. Politics resets every five years, but the poverty stays where it is.

The saddest part is how normalised it all feels. Welfare has become the ceiling of aspiration, not the floor. People do not expect the state to create jobs; they expect the state to compensate for the absence of jobs. They do not expect good schools; they expect coaching subsidies. They do not expect reliable public health; they expect insurance reimbursements. They do not expect industries; they expect loans and waivers. This is not prosperity. It is the politics of low expectations.

And that is why watching the victory euphoria is less about one party’s triumph and more about the déjà vu of an annuity-based democracy — manifesto, wave, massive mandate, cabinet, scandal, and another election where the same families in the same villages line up for the same promises.

But the story need not end there.

Because the future of Bihar — and perhaps the Republic — will not be shaped on an election night in Patna. It will be shaped in thousands of quieter decisions: a panchayat insisting that the primary school actually functions; a district choosing to fix health centres before building statues; a government prioritising industrial clusters over new cars for ministers; a voter asking not “what will I get tomorrow?” but “what has changed in ten years?”

The real victory will come when a young graduate in Siwan finds a job without migrating, when a child in Motihari completes Class XII without dropping out, when a farmer in Darbhanga is not ruined by the monsoon, and when politics stops treating poverty as a vote bank and starts treating dignity as a right.

Until then, Bihar will remain caught in this paradox — the richest history, the poorest present, and an uncertain future subsidised by everyone except its own leaders.

Politics for poverty is not a model; it is a warning. And last night’s celebrations, however joyous, were only the preface. The morning after is where Bihar’s story will truly be written.