Europe Watches Ukraine — and Rearms

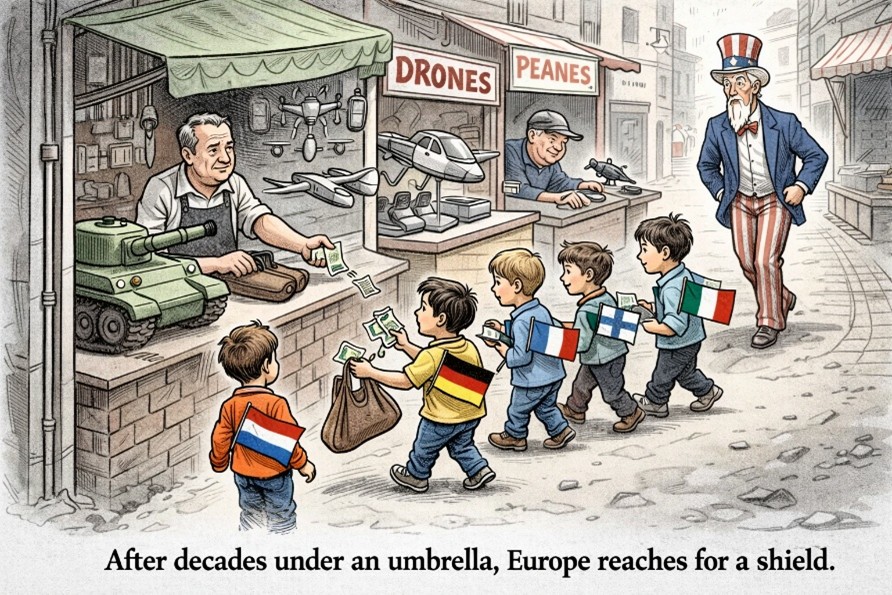

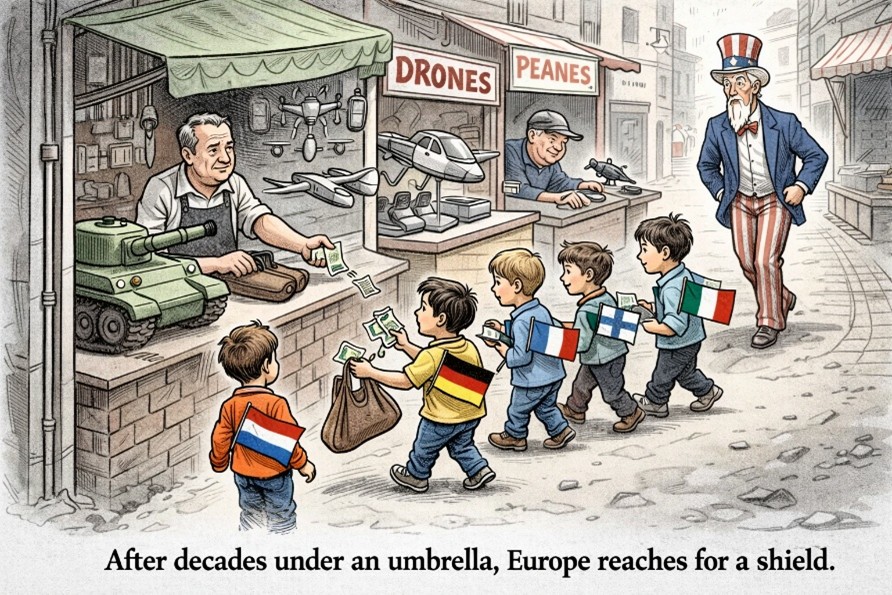

Not ambition, but anxiety is driving a historic military shift

At the Munich Security Conference this week, European leaders spoke of strengthening their own defence capability. It sounded like a routine policy discussion.

It was not.

For nearly eight decades Europe lived under a quiet but extraordinary arrangement: the United States would guarantee security, and Europe would build prosperity. The continent that produced two world wars chose a different civilisation model — fewer armies, more institutions; fewer fortresses, more welfare states.

Today that assumption is changing.

And the reason is not military ambition.

It is fear.

Why Europe once abandoned militarism

In 1945 Europe was not simply defeated — it was exhausted. Cities lay in ruins, industries collapsed, currencies were unstable and societies traumatised. Two devastating wars within thirty years convinced European leaders that traditional power politics among European nations had become suicidal.

At that moment two powers stood strong: the United States and the Soviet Union.

Western Europe made a deliberate decision. Instead of competing militarily, it would integrate economically. The Marshall Plan rebuilt industry. The European Coal and Steel Community — the precursor to the European Union — placed the very industries of war under shared management so France and Germany could never secretly rearm against one another.

Security came from NATO. American troops, bases and nuclear deterrence protected the continent. Europe, in return, invested in reconstruction, education, public health and social protection.

Peace was not merely hoped for.

It was designed into the system.

The long peace — and the belief behind it

After the Cold War ended in 1991, that belief deepened. Borders opened, trade expanded and even Russia became an energy partner. Economic interdependence seemed to make war irrational.

Defence spending steadily fell across much of Europe. Many countries remained below the NATO guideline of 2% of GDP on defence. Conscription disappeared. Military industries shrank.

The assumption was simple: large-scale war in Europe had become unthinkable.

Ukraine changed that

The Russia–Ukraine war shattered not only borders but certainty.

For the first time since the 1940s, a prolonged conventional war returned to the European continent. It did not end quickly. Energy shortages followed. Inflation rose. Refugees moved across borders. Supply chains were disrupted.

More importantly, Europe saw something unsettling:

a sovereign country in Europe could still face invasion.

Germany responded by creating a €100-billion defence fund — its largest military policy shift since World War II. Poland began expanding one of Europe’s largest armies. Several NATO nations pledged to reach or exceed the 2% defence spending benchmark. Global military expenditure has now crossed about $2.2 trillion annually, the highest in history.

As NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg said,

“Peace is not free.”

The war also changed technology priorities. Ammunition production lines are reopening. Drone warfare, cyber capability and air defence systems are becoming central to policy. Defence industry, once declining, is now strategic again.

What Europe truly fears

Europe is not preparing to fight Russia tomorrow.

It is preparing for uncertainty.

For decades, security was effectively delegated to the United States. That arrangement worked as long as the international order was stable. But the Ukraine war revealed a difficult reality: economic ties, energy trade and financial integration do not necessarily prevent conflict.

Europe now worries about vulnerability — what happens if external protection weakens, or global politics becomes unpredictable?

Ukraine, in this sense, is not just a conflict zone.

It is a warning.

The question Europeans are asking is not whether they want war.

It is whether they are prepared if peace fails.

The larger lesson

The European Union was the great political experiment of the twentieth century — replacing rivalry with cooperation. The present shift toward defence does not signal abandonment of that idea; it signals recognition of its limits.

Prosperity alone cannot guarantee stability. Institutions alone cannot deter aggression. Peace requires not only agreement but resilience.

The moral extends beyond Europe. Any society that assumes stability is permanent eventually confronts the need to protect it. Security outsourced indefinitely becomes security uncertain.

The war in Ukraine will someday end, as wars eventually do.

But its deeper effect has already begun.

Europe is rediscovering something history repeatedly teaches: peace survives not merely because nations desire it, but because they are prepared to preserve it.