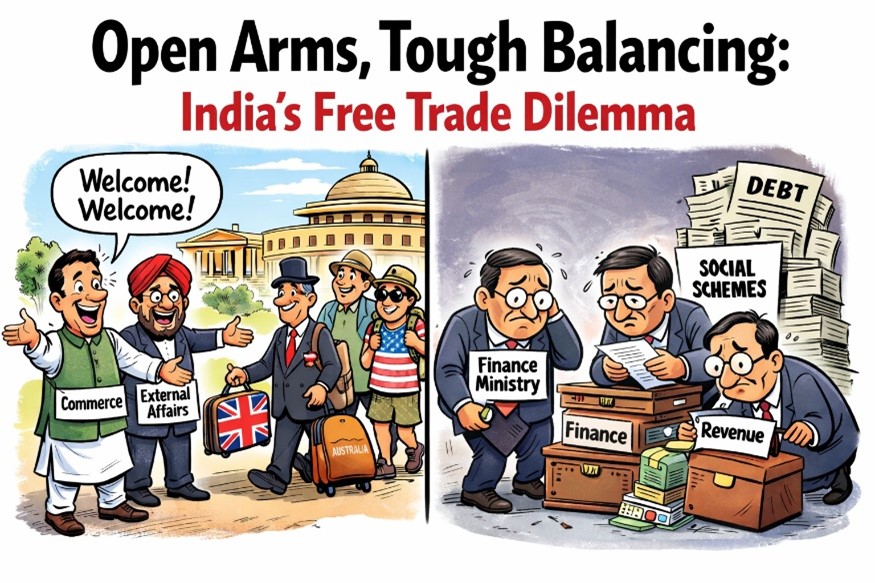

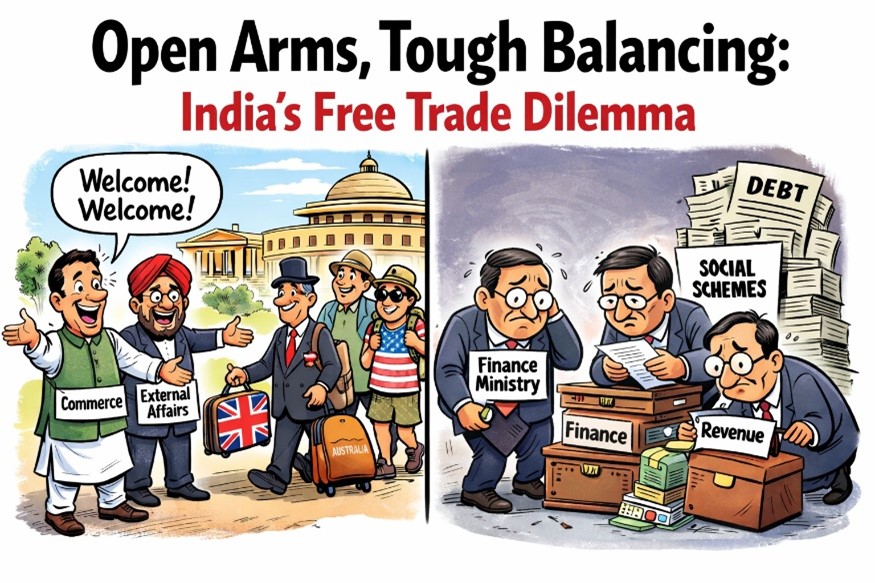

Lower duties, higher devolution, rising welfare — a convergence the Budget cannot ignore

By Ravishankar Kalyanasundaram

India is opening its doors to the world at a moment when its own fiscal floor is under strain.

Free Trade Agreements with Australia and the UK are already in force. The long-awaited agreement with the European Union has finally been concluded. Talks with the United States are progressing quietly but purposefully. The stated objective is sensible and strategic: integrate Indian enterprise with global value chains, expand exports, lower input costs, and give industry the scale it needs to compete.

But trade policy does not operate in a vacuum. Every tariff lowered, every customs duty removed, also reduces a line item in the Union government’s revenue ledger — and that ledger is already stretched.

Customs Duties: Small Share, Big Consequence

Customs duties today account for less than four per cent of total Union government receipts. On paper, this looks manageable. In practice, it is not.

In absolute terms, customs collections still run into several lakh crore rupees annually, and — more importantly — they are among the most predictable sources of revenue. FTAs dismantle this predictability. Once tariffs go to zero, the revenue is not deferred; it is permanently foregone.

The India–UK FTA alone is expected to reduce customs revenue by over ₹4,000 crore in the first year, with the loss widening as more tariff lines are phased out. The EU agreement is far larger in scale. India has committed to eliminate or sharply reduce duties on over 90 per cent of tariff lines, covering nearly all traded goods over time. Add Australia, ASEAN concessions, and a potential US deal, and the cumulative erosion becomes material.

At the same time, customs exemptions and concessions already cost the exchequer over ₹4 lakh crore annually — a number that has steadily risen even before the newest FTAs take full effect.

GST Will Not Magically Fill the Gap

The counter-argument has been that GST will compensate. That assumption is increasingly fragile.

Yes, GST collections have grown, aided by better compliance and digital enforcement. But GST rates have also been rationalised downward to support consumption and ease inflationary pressures. Independent estimates suggest that recent rate cuts have resulted in tens of thousands of crores in annual revenue loss, only partly offset by higher volumes.

GST growth is cyclical; tariff loss is structural. Confusing the two is a fiscal mistake.

Finance Commission Transfers and the Shrinking Centre

Compounding the pressure is the increasing share of central taxes devolved to states, following Finance Commission recommendations. States now receive a significantly higher proportion of divisible tax revenues — a welcome move for federal balance, but one that leaves the Centre with less fiscal headroom.

This would be manageable if state finances were robust. They are not.

Several states are already under severe fiscal stress — borrowing not to invest, but to meet salaries, subsidies, and interest payments. Their deficits increasingly mirror the Centre’s anxieties. The result is a Republic where both tiers of government are financially constrained at the same time, even as demands on them rise.

The Rupee Problem No One Can Ignore

Then there is the rupee.

A depreciating rupee does not merely affect importers’ margins; it directly hits the sovereign balance sheet. India continues to import the bulk of its energy — oil, gas, fertiliser inputs — in dollars. Every rupee slide automatically inflates the import bill, fuels domestic inflation, and tightens monetary conditions.

The irony is stark: as tariffs fall and revenues weaken, energy import costs rise, draining fiscal resources further. This is not a theoretical risk. It is already visible in subsidy burdens and inflation management.

Populism Without a Funding Map

Against this backdrop, political commitments continue to expand.

Guaranteed employment schemes stretching to 150 days, free health coverage, subsidised food, electricity support, and a growing web of state-level doles are all morally defensible — but fiscally expensive. None come with a clear funding roadmap that accounts for shrinking customs revenues, moderated GST growth, and rising interest costs.

Borrowing can bridge the gap — but only temporarily. Public debt is already elevated, and servicing costs rise with every external shock.

The Investment India Cannot Postpone

What makes this moment especially delicate is that India cannot afford to under-invest.

To remain competitive in global trade, the country urgently needs shared national infrastructure for:

These are not luxuries. They are the entry ticket to future trade. Individual firms cannot build this alone. The State must act as platform-builder — just as it once did with ports, power and telecom.

At the same time, India must invest in large-scale reskilling, particularly in rural and semi-urban areas, to prevent a demographic dividend from turning into a social liability.

A Moment for Fiscal Honesty

India’s free-trade ambition is directionally right. But ambition without fiscal realism is dangerous.

Lower tariffs, higher state transfers, a weaker rupee, rising welfare commitments, and postponed strategic investment together form a pressure system that cannot be wished away. Something has to give — either spending discipline improves, revenue strategy broadens beyond GST, or public investment priorities are ruthlessly focused on sectors with the highest long-term returns.

The Republic has reached a point where trade policy, welfare policy, and fiscal policy can no longer be discussed separately. They are now inseparable threads of the same fabric.

History shows that nations do not stumble at moments of scarcity alone. They stumble when generosity outruns capacity and optimism outruns arithmetic.

India still has time to recalibrate. But the window for honest choices is narrowing.