History realigns quietly, through necessity disguised as prudence.

By Ravishankar Kalyanasundaram

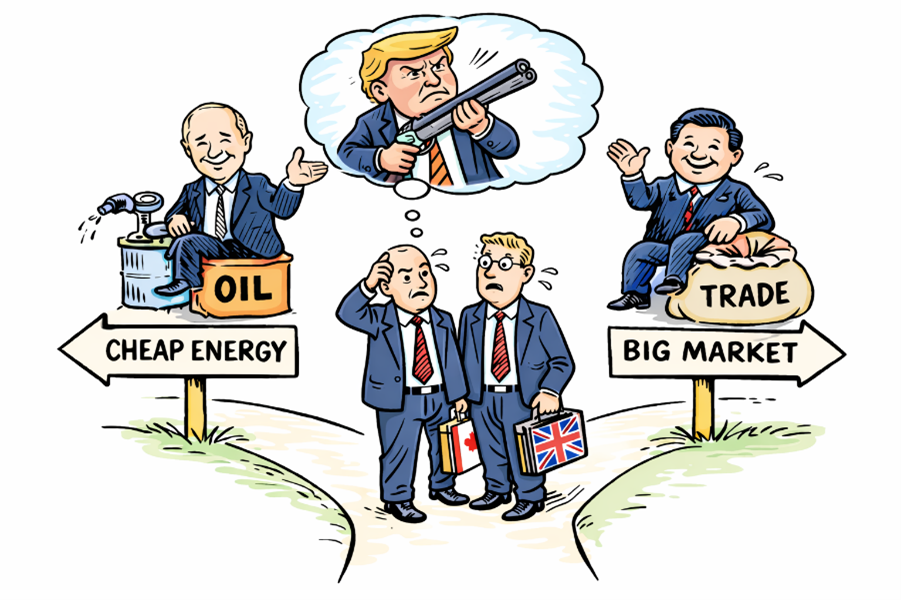

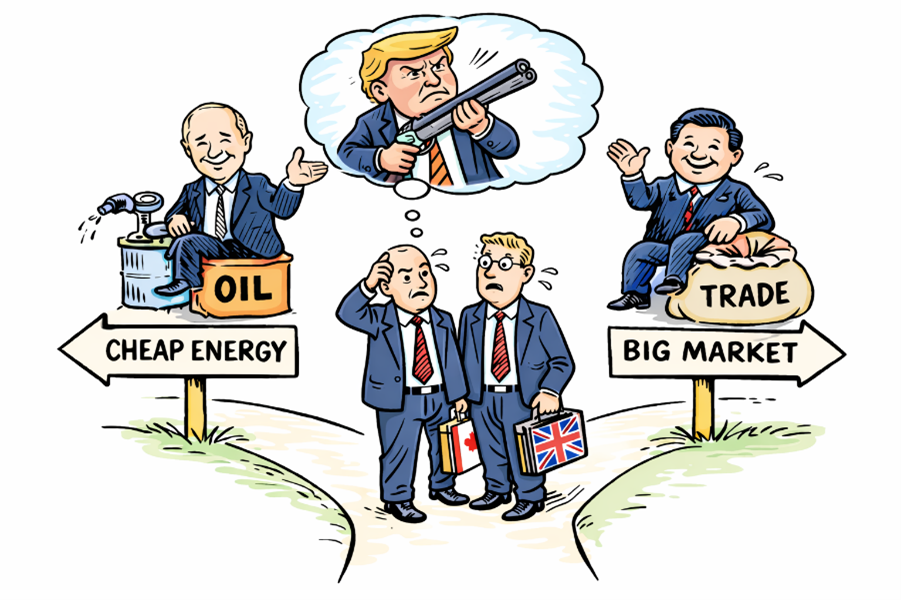

When UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer arrived in Beijing this week, it was more than a delayed diplomatic courtesy. It was a signal. Coming soon after Canada’s outreach, it marked a visible recalibration: Western leaders returning to China after years of deliberate distance. Not with warmth. Not with trust. But with necessity.

For much of the past decade, China was treated as the world’s strategic discomfort—too large to ignore, too assertive to embrace, too central to isolate without cost. The West spoke of “de-risking” and “values-based alignment,” as though global supply chains could be morally curated without consequence. That assumption is now colliding with reality.

The dragon, it turns out, never left. The world simply tried—and failed—to look away.

China’s distancing was not sudden. It evolved steadily after the global financial crisis of 2008. While Western economies staggered, China built—roads, ports, factories, and confidence. The Belt and Road Initiative followed, along with a more assertive presence in technology, finance, and regional security. Tensions over trade practices, intellectual property, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and the South China Sea hardened positions. Language shifted. China was no longer a “partner” but a “systemic rival.”

COVID-19 sealed the estrangement. Supply chains were recast as vulnerabilities. Semiconductors became strategic assets. Diplomacy acquired a moral edge. The ambition was simple: integrate China economically while constraining it strategically.

But history rarely tolerates neat contradictions.

Even at the height of political distance, trade never stopped. Containers moved. Factories hummed. Western consumers continued to depend on Chinese manufacturing, even as leaders spoke of decoupling. Rhetoric ran ahead of reality.

There was precedent for this discomfort. In the 1970s, the United States opened relations with Mao’s China not out of ideological sympathy, but strategic fear—fear of a Soviet-dominated Eurasia. Kissinger’s secret trip to Beijing was driven by balance, not belief. Geometry mattered more than doctrine.

Today’s return follows the same logic, only the pressures are broader.

Economically, China remains irreplaceable—not merely as the world’s factory, but as one of its largest markets. European manufacturers are discovering that growth without China is arithmetic fiction. Britain, navigating a post-Brexit world, feels this compulsion even more sharply.

Politically, alliances feel less settled. The United States is increasingly transactional. Europe is distracted by internal strain and war fatigue. Middle powers are hedging, unwilling to be caught between unpredictability in Washington and absence in Beijing. Canada’s visit was not symbolic; it was survivalist.

Militarily, the atmosphere has thickened. Ukraine has drained arsenals and attention. Taiwan remains unresolved. The South China Sea simmers. History teaches a blunt lesson: escalation without communication is how miscalculation begins. Even adversaries need rooms with doors, not megaphones.

China understands this leverage. It does not seek Western approval. It seeks Western presence—on terms that acknowledge its weight.

Which brings us to the question few ask aloud, but many are quietly calculating. If Western leaders can return to Beijing under economic and strategic compulsion, will a similar procession one day find its way—directly or indirectly—to Moscow?

The answer, stripped of theatre, is yes. Slowly. Quietly. Reluctantly.

History rarely announces its turns with trumpets. It realigns quietly, through necessity disguised as prudence.

Which brings us, inevitably, to the old aphorism: saints have a past, and sinners a future. In geopolitics, the trouble lies not in the phrase but in the labelling. Everyone arrives wrapped in selective memory and borrowed virtue. The saint of today was yesterday’s pragmatist; the sinner of today may yet become tomorrow’s indispensable partner. The real difficulty, as always, is not deciding whether to engage—but agreeing, conveniently and collectively, on who is the saint, and where is the sinner.