“It took faith to build this system. It takes care to keep it.”

Sukumar Sen, India’s first Chief Election Commissioner, oversaw a democratic undertaking that would have daunted even the most advanced nations. He did so not with abundance, but with belief. Belief that every citizen—regardless of education, wealth, caste, gender, or geography—had a stake in the Republic. In a country where barely a quarter of the population could read or write, ballots were cast using symbols, wooden boxes, and trust. That quiet miracle—the successful conduct of India’s first general election—laid not merely an administrative framework, but the moral foundation of Indian democracy.

Decades later, T. N. Seshan reminded the political class that this foundation was not ornamental. It was constitutional. He asserted the authority of the Election Commission when it was convenient for no one. He was confrontational, often abrasive, and deeply unpopular with political parties across the spectrum. But he restored a central truth: elections are not a negotiation between convenience and power; they are an obligation owed to the Republic.

The institution today stands on the shoulders of these giants. To treat it casually—or worse, to delegitimise it recklessly—is to forget the distance travelled, the terrain crossed, and the faith invested by generations of voters.

This is not an argument against scrutiny. Allegations of wrongdoing must be examined. Errors must be corrected. Transparency must be strengthened. If there are doubts, they must be addressed through evidence, audit, judicial oversight, and institutional reform. Democracies mature by questioning their systems—not by burning them down.

But there is a line between vigilance and vandalism.

In recent years, the Election Commission has found itself operating in an atmosphere thick with suspicion and sharpened by polarisation. Political parties now attack one another with an intensity that leaves little room for nuance, and the Commission—once an aloof constitutional referee—often finds itself dragged into the crossfire. Accusations fly freely: that transfers of officials favour one side, that enforcement of the Model Code of Conduct appears uneven, that press briefings sound defensive rather than confident. To some critics, the Commission today looks less like the thunderous authority of the Seshan era and more like a cautious bureaucracy navigating political storms without bruising itself.

These criticisms cannot simply be dismissed. Perception matters, because democracy itself is an act of collective belief. But it is equally important to recognise the constraints under which the Commission operates—constraints rarely acknowledged in public debate.

The Election Commission has no standing army of its own. It commands no permanent cadre on the scale its task demands. Every election is conducted with borrowed people—teachers, clerks, engineers, revenue officials—pulled from their regular duties and asked to become neutral arbiters for a few intense weeks. Security depends on state and central forces that ultimately report to elected governments. Budgets are sanctioned elsewhere. Infrastructure is improvised, not owned. The Commission’s authority is constitutional, but its capacity is contingent. To demand perfection from such an institution, while denying it autonomy, resources, and public trust, is to impose expectations without responsibility.

More troublingly, the Commission alone cannot carry the burden of a political system that is itself under severe strain. A deeper crisis shadows India’s electoral landscape—one no procedural reform can fully conceal. Politics is being criminalised at a pace that alarms even seasoned observers. Candidates facing serious criminal charges continue to win elections by commanding margins. Voters, often trapped between limited choices, rationalise compromise as inevitability.

Money power has grown so brazen that election spending increasingly resembles a financial festival rather than a democratic exercise. The crude cash handout has evolved into sophisticated financial engineering—digital transfers, layered intermediaries, inducements disguised as welfare, influence routed through invisible networks. Simultaneously, political parties in state after state have slipped into family control. Internal democracy is quietly extinguished, dissent punished, and organisations reduced to private estates rather than public institutions.

Elections, once celebrations of the Republic, increasingly resemble high-stakes carnivals where technology, money, and messaging overwhelm substance.

The rise of social media has intensified this transformation. Elections are no longer fought only on roads, stages, and newspaper columns. They are waged in encrypted groups, algorithmic feeds, and carefully engineered echo chambers. WhatsApp forwards, deepfakes, influencer armies, micro-targeted propaganda, and online mobs now shape voter perception long before campaigns formally begin. The Election Commission, designed for a physical world of rallies and posters, now faces an algorithmic battlefield where misinformation travels faster than any clarification. A rumour can reach millions in hours; an official rebuttal may reach only a fraction, often too late.

And yet—this is the paradox that deserves far more attention—through all this turbulence, the Indian voter remains astonishingly resilient.

Turnout continues to rise. Women vote in larger numbers than ever before. Youth, despite cynicism and fatigue, still stand in queues on polling day. Rural India often votes with greater enthusiasm than its cities. The spirit of democracy survives not because the system is perfect, but because citizens refuse to abandon it. They show up. They wait. They mark their choice. They believe, however cautiously, that the vote still matters.

This resilience was forged in hardship. It was earned when ballots travelled on bullock carts and boats, when polling booths stood under trees, when election officers crossed rivers and forests with wooden boxes tied in rope. That memory matters. It reminds us that democracy in India was never easy—and never guaranteed.

This is why the Election Commission’s reinvention is not a bureaucratic exercise, but a national necessity. The institution must reclaim the stature it once commanded—independent, fearless, technologically equipped, and constitutionally unshakeable. It must expand its understanding of electoral malpractice to include digital manipulation, financial engineering, and psychological targeting. It must work with institutions such as the CAG, RBI, and enforcement agencies not to harass political actors, but to ensure clean and transparent political funding. It must modernise monitoring, protect whistleblowers, strengthen field machinery, and ensure that no booth, no district, no citizen feels abandoned by the system.

Yet even this may not be enough.

The hardest questions remain unresolved. Can honest politics survive when elections demand enormous funding? Can principled leadership emerge when the path to power is paved with patronage? Can internal democracy flourish when political parties function as family trusts? Can any election commission—however independent, however empowered—cleanse a political bloodstream that society itself has allowed to corrode?

These are uncomfortable questions because they turn the mirror inward.

As India approaches another electoral cycle, the Election Commission must once again act as custodian of faith. It must reassure the voter that the booth is free, the process fair, and the outcome belongs only to the people. Whether it can do so in an era of unprecedented turbulence is one of the defining challenges of our time.

But an equally important question lies beyond the Commission’s control.

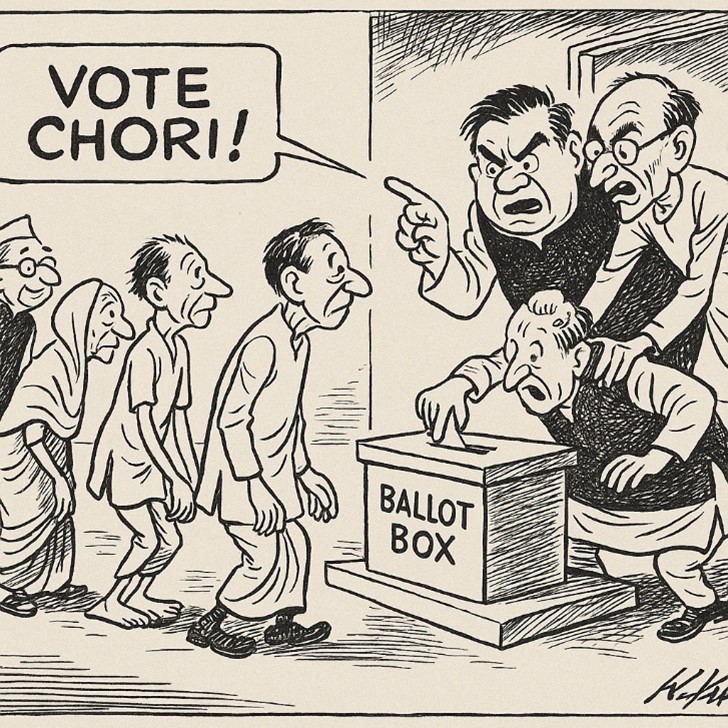

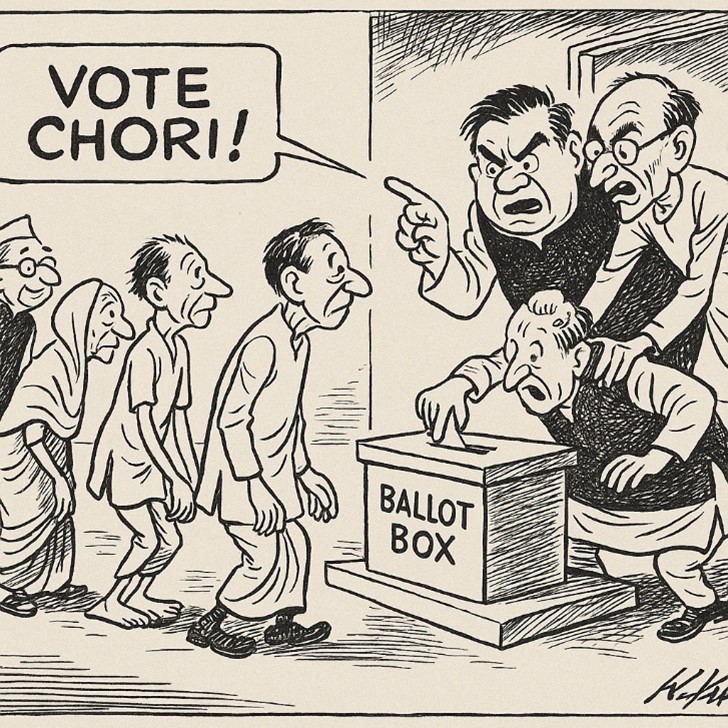

Yes, we must examine allegations. Yes, we must demand accountability. Yes, we must ask whether everything is well. But before we rush to the microphone shouting vote chori, we must ask a harder, more honest question: is this only their job—or is it ours?

Democracy is not protected by institutions alone. It survives because citizens choose restraint over rage, reform over ridicule, and responsibility over convenience. The road ahead is long. There are miles to travel. And we will not finish this journey by pointing fingers alone.

This is the heart of our Republic.

Still unfinished.

And still ours—together.