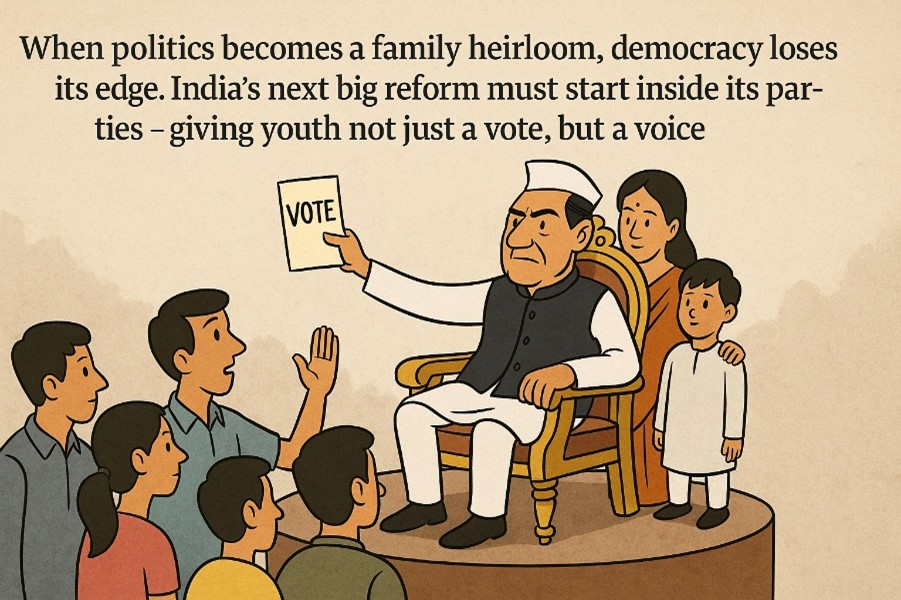

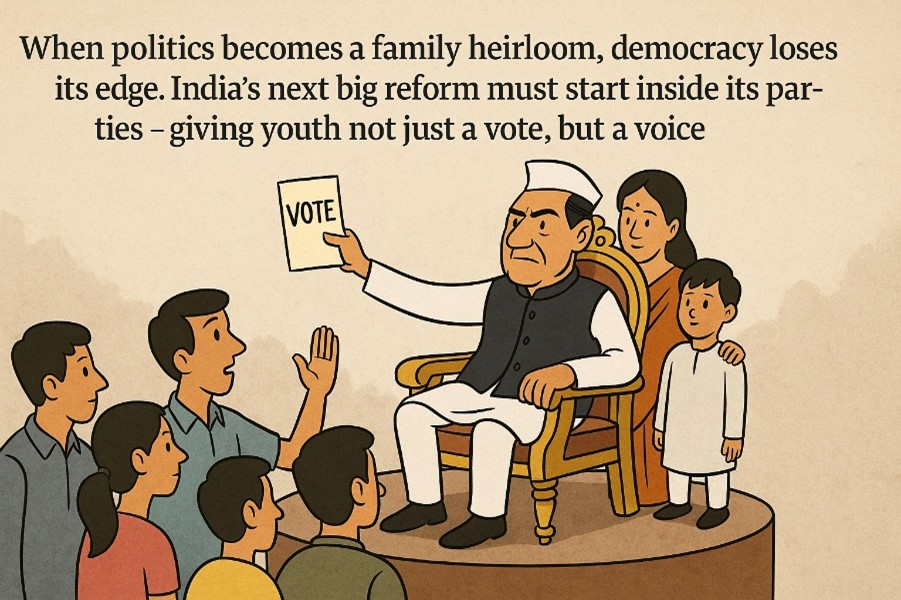

When politics becomes a family heirloom, democracy loses its edge. India’s next big reform must start inside its parties — giving youth not just a vote, but a voice.

By Ravishankar Kalyanasundaram

A democracy of familiar faces

A familiar media report: one family party demands to be projected as the Chief Minister candidate, another family consents, and the alliance submits. The media accepts this, we accept this — and it has become as routine as a weather report. What once would have stirred debate now barely raises an eyebrow.

Yet, beneath this routine lies something deeper — a slow dulling of our democracy’s edge. Every time a seat is decided across dining tables of family homes rather than through party elections, a little more of India’s political promise drains away. What does this say to the millions of young Indians who dream of leadership but see no ladder to climb? That politics is not a career, but an inheritance?

From a movement to a family tree

This wasn’t how India’s democracy began. When the Indian National Congress was born, it drew its strength from argument, debate, and the faith that a nation of millions could decide its own destiny. But somewhere between the freedom struggle and the coalition age, our parties turned into family businesses. Control of party funds, access to media, and the power to give election tickets all began to gather around surnames rather than ideas.

The Congress, of course, pioneered the model — first under Nehru, then Indira Gandhi, and down the generations. But it didn’t stop there. Almost every major state has its own political dynasties now, from north to south, ruling parties and opposition alike. Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra — each has families whose names have become fixtures on the ballot. Today, nearly one in five of India’s elected representatives belongs to a political family. It’s no longer an exception; it’s the rule.

Why it happens — and why it hurts

It’s easy to see why this happens. In a country of 1.4 billion, name recognition is currency. A known family means easier funding, quicker mobilisation, and instant voter familiarity. Parties, hungry for quick wins, treat dynastic faces as safe bets. But what’s easy for the party may not be right for the country. When political power passes like inheritance, it blocks fresh energy and new talent.

The young and the shut-out

India is a young country. Half its population is under thirty. Yet, less than eleven percent of our MPs are below forty. For a nation that prides itself on youthful ambition, our politics looks curiously old and inherited. The message it sends to young Indians is devastatingly simple: if your last name doesn’t already carry political weight, your chances are slim. So many bright, idealistic people — the kind who should be shaping India’s future — never even consider politics as a career.

Where corruption finds its comfort

And where leadership is inherited, corruption often finds quiet comfort. In family-run politics, loyalty is not always measured by integrity or performance, but by proximity to the circle of influence. The flow of funds, contracts, and appointments starts to follow the same path as power — upwards, and inward. Projects meant for the public good are too easily re-routed through channels of favour and familiarity. Highways, industrial parks, and irrigation schemes that should symbolise national progress risk becoming private estates of patronage.

Over time, corruption stops shocking us; it becomes the lubricant that keeps the network intact. When political advancement depends more on maintaining relationships than on serving citizens, the incentive to govern cleanly weakens. Every blurred account, every quiet favour, is treated not as a violation but as a nod to the culture of convenience. And with that, politics drifts further away from public duty — towards the subtle art of preserving privilege.

When governance becomes inheritance

This family hold doesn’t just hurt ambition; it weakens governance. When parties function like private firms run by one household, accountability shrinks. The inner circle gets smaller. Debate becomes dangerous. Loyalty counts more than competence. And policy begins to revolve around keeping the network alive — rather than keeping the nation ahead. It’s a silent tax that we all pay, measured in slower reforms, weaker institutions, and public cynicism.

A global pattern, an Indian twist

What’s tragic is that this pattern is not unique to India. Democracies across the world have their dynasties — the Kennedys and Bushes in America, the Bhuttos in Pakistan, the Lees in Singapore, the Abes in Japan. But in most of those places, party systems remain strong enough to outlive the family. In India, the family often outlives the party. That’s the real danger — when institutions fade, and legacies take their place.

Opening the gates again

Yet, it doesn’t have to be this way. Every generation produces new voices eager to serve, if only the gates were open. India’s youth today are educated, connected, and politically aware in ways their grandparents never were. They see inequality, corruption, and opportunity up close. Many want to fix what’s broken, but the system seems designed to keep them out. Unless parties begin to change from within — holding real internal elections, mentoring younger leaders, letting new ideas breathe — democracy will remain trapped in a generational loop.

A democracy that must renew itself

The irony is that our democracy, which once freed us from colonial rule, now needs to free itself from inherited rule. The family name may still win elections, but it can no longer win the future. For India to grow, politics must again become a field of aspiration, not inheritance.

One day, perhaps soon, the nation will look up to a new generation — young men and women who step into politics not because they were born into it, but because they earned it. When that happens, democracy will feel truly ours again.