The Silent Hazard of the Device We Cannot Put Down

By Ravishankar Kalyanasundaram

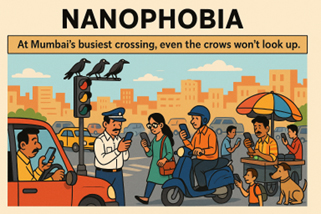

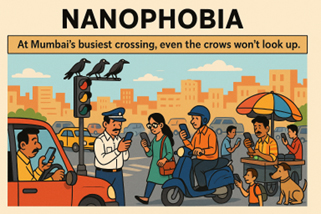

A striking headline in The Guardian this past week reported that Sweden will implement a nationwide ban on mobile phones in all schools from 2026, arguing that constant digital distraction is harming focus, safety, and mental health . It was not about geopolitics or economics, but about something closer to our palms: the hidden toll of the mobile phone. The very tool that made modern life simpler is also quietly spawning a wave of social and medical concern. Call it Nanophobia—fear of the invisible, silent hazards of an invention we cannot live without.

A Device More Common than Humanity

There are now more mobile phones than human beings—over 8.5 billion subscriptions in a world of 8.1 billion people. No invention in history has spread so far, so fast. The automobile took 80 years, television 50; the mobile phone did it in two decades.

Economically too, the numbers are staggering. The combined market valuation of handset makers and telecom service companies is measured in trillions. Apple’s market valuation recently crossed USD 3 trillion — larger than the GDPs of many countries including France and Italy, and nearing that of India. Add China Mobile, AT&T, Reliance Jio, and the rest, and global telecom services generate revenues of over USD 1–2 trillion a year—about 1–2% of world GDP. That is still larger than many traditional industries and has become a backbone of the modern economy. Nations fight fiercely to host factories: India has pushed Apple’s suppliers to expand production, with exports now forming a significant chunk of its foreign exchange earnings. Vietnam and Thailand compete for the same prize. Phones, once consumer items, are now instruments of national strategy.

The Office in Your Pocket

The phone has shrunk the office into our palm: camera, calculator, compass, and bank rolled into one. In villages without banks it is a wallet; in classrooms without books it is a teacher. No other device has democratized access so powerfully.

But alongside utility has come intimacy. As Jane Vincent’s research notes, the mobile phone is “a conduit for emotional attachment”

People keep old phones under pillows because the text messages feel too precious to delete. We panic when batteries die, clutch phones in crises, and feel oddly reassured that loved ones are clutching theirs at the same time. It is not just a tool—it has become an extension of identity.

The Psychological Grip

Psychologists warn that this intimacy has turned into entrapment. Psychology Today called it “the slot machine in your pocket”—random bursts of messages and likes hook the brain into compulsive checking. Phantom vibrations, midnight scrolling, and “absent presence” at the dinner table have become everyday behaviours.

More troubling is how children are now caught in the spiral. Across Europe, children as young as 10 are being treated for phone addiction in clinics. In the U.S., paediatricians report rising cases of screen-induced anxiety and sleep disorders. In India, counselling centres have opened for teenagers unable to detach from gaming apps and endless scrolling. The World Health Organization lists internet gaming disorder as a clinical concern, and many psychiatrists argue that smartphone addiction is next in line.

Anxiety and Addiction on the Rise

The global numbers are sobering. In the past decade, the prevalence of anxiety disorders has risen nearly 25% worldwide, with clinicians pointing to digital overload as a contributing factor. Among adolescents, cases of diagnosed depression and anxiety have doubled in several countries. Hospitals in South Korea and Japan run special wards for “internet rescue therapy,” where children are detoxed from devices under supervision. Similar trends are now visible in Europe and the U.S.

We once thought addiction was about alcohol, tobacco, or narcotics. Now the glowing rectangle in our hands—legally sold, socially admired, and economically celebrated—has joined that list.

The Health Question

For years scientists have debated whether long-term exposure to radiofrequency radiation is harmful. Regulators insist emissions are within safe limits. Yet independent studies raise flags about sleep disruption, reduced fertility, and possible links to neurological disorders. None are conclusive, but taken together they evoke an uncomfortable déjà vu—like the early debates on tobacco in the 1950s or leaded petrol in the 1970s.

Beyond radiation, there are subtler biological effects: blue light disturbs circadian rhythms, posture damage from “text neck” is rising, and dopamine circuitry is rewired by constant scrolling. We are living inside a global, unregulated experiment whose outcomes will only be clear decades later.

Can We Step Back?

Some countries are trying. France bans phones in primary schools. China limits online gaming hours for children. Silicon Valley parents quietly send their own children to phone-free schools. Sweden’s national ban may be the boldest move yet. But these are exceptions. For most of the world, phones remain too deeply embedded in commerce, governance, and daily survival to restrict.

A Wise Pause

The answer may not be rejection but balance. Phones must serve us, not enslave us. Societies will need deliberate choices: phone-free hours in families, no-screen nights in schools, urban spaces where conversation is uninterrupted.

History shows that every invention—fire, the automobile, even plastic—carries hidden hazards. The phone is no different. What sets it apart is speed: never before has an invention conquered the world before its risks were fully known.

Nanophobia, then, is not irrational fear. It is the necessary caution of a society dazzled by convenience but wary of invisible costs. The greatest danger is not radiation or blue light, but our quiet surrender of time, attention, and childhood to a machine.

Perhaps the wisest remark is this: when a tool becomes a master, it is not technology we should fear, but ourselves.